- Home

- Angry by Choice

- Catalogue of Organisms

- Chinleana

- Doc Madhattan

- Games with Words

- Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

- History of Geology

- Moss Plants and More

- Pleiotropy

- Plektix

- RRResearch

- Skeptic Wonder

- The Culture of Chemistry

- The Curious Wavefunction

- The Phytophactor

- The View from a Microbiologist

- Variety of Life

Field of Science

-

-

Change of address7 months ago in Variety of Life

-

Change of address7 months ago in Catalogue of Organisms

-

-

Earth Day: Pogo and our responsibility10 months ago in Doc Madhattan

-

What I Read 202411 months ago in Angry by Choice

-

I've moved to Substack. Come join me there.1 year ago in Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

-

-

-

-

Histological Evidence of Trauma in Dicynodont Tusks7 years ago in Chinleana

-

Posted: July 21, 2018 at 03:03PM7 years ago in Field Notes

-

Why doesn't all the GTA get taken up?7 years ago in RRResearch

-

-

Harnessing innate immunity to cure HIV9 years ago in Rule of 6ix

-

-

-

-

-

-

post doc job opportunity on ribosome biochemistry!11 years ago in Protein Evolution and Other Musings

-

Blogging Microbes- Communicating Microbiology to Netizens11 years ago in Memoirs of a Defective Brain

-

Re-Blog: June Was 6th Warmest Globally11 years ago in The View from a Microbiologist

-

-

-

The Lure of the Obscure? Guest Post by Frank Stahl13 years ago in Sex, Genes & Evolution

-

-

Lab Rat Moving House14 years ago in Life of a Lab Rat

-

Goodbye FoS, thanks for all the laughs14 years ago in Disease Prone

-

-

Slideshow of NASA's Stardust-NExT Mission Comet Tempel 1 Flyby15 years ago in The Large Picture Blog

-

in The Biology Files

AW#37: Sexy Geology on the Beach

The sun, the beach and sexy geology…

You can find marls with cycles, layers of a hotter time, faded traces of bodies and the coolest men alive...

Humboldt´s Cosmos

"Inside the globe there live mysterious forces, whose effects become apparent on the surface. Outbreaks of vapours, hot slag and new volcanic rocks, as uplifts of islands and mountains"

Alexander von Humboldt

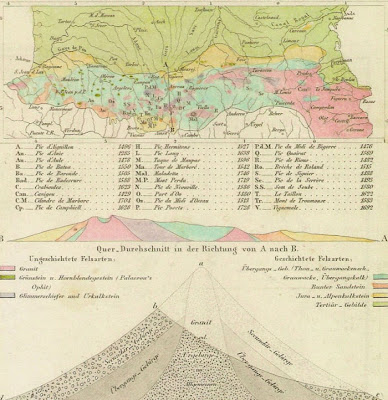

Fig.1. Geologic map and profile of the Pyrenees, after the "Berghaus-Atlas", a supplement to Humboldt's masterpiece "Kosmos" (1845-1862).

Fig.1. Geologic map and profile of the Pyrenees, after the "Berghaus-Atlas", a supplement to Humboldt's masterpiece "Kosmos" (1845-1862).

In the profile from inside to the outside of the mountains the layers are described as follows "Granitic rocks and general basement" - "transition mountains/rocks" - "secondary mountains". In the map Granite=pink, Basaltic rocks=green, Schist= grey, Clastic rocks/ Limestone= blue, Sandstone= red, Secondary Limestone= yellow, Tertiary rocks= dark-green

The German Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) studied finance and also mining engineering and became later a great self-educated explorer and naturalist. Following the tradition prevalent in Germany at the time he was educated to interpret geology with Werner's Neptunism - rocks were formed from liquids and magmatic phenomena are only of local significance.

During his travels in Europe and America he observed also active volcanoes and soon converted to Plutonism - rocks are formed from cooling lava and magmatic forces play a mayor role in shaping earth's surface.

In accordance to the theory of German geologist Leopold von Buch (1774-1835) of "volcanic bubbles" the profile shows the Pyrenees as a result of uplift by a core of magmatic rocks, bending the sedimentary layers of sandstone and limestone formations. According to this hypothesis magmatic rocks are found always as core in mountain ranges. To explain the apparent lack of Grantic rocks (coloured in pink) in the northern areas of the Pyreenes Humboldt apparently suggested selective erosion - explained by the schematic profile at the bottom of the page.

The Pyrenees are a mountain range 1500km long with an average width of 200km, the most western foothills of the Alpine-Himalayan orogenic belt. According to the modern theory of plate tectonics these mountains formed when the Iberian plate was partly subducted under the European plate, in a time period from the late Cretaceous to the Miocene (55-25 Ma).

The profile of the Pyrenees display a fan-shaped structure, with north vergent thrusts in the northern area and south vergent thrusts in the southern part.

In northwest to southeast direction the mountain range can be divided into five structural zones

- The Aquitaine foreland basin with the deformed Cretaceous sediments of the European Plate.

- The North Pyrenean thrust zone with thrust faults developed in the crystalline basement and the Mesozoic to Eocene sediments.

- The Axial zone with three mayor nappes of the crystalline basement

- The South Pyrenean thrust zone with deformed early Eocene to Miocene sediments.

- The Ebro foreland basin molassic, filled with relatively undisturbed sediments.

Fig.2. Axial Zone: Variscan granitoid rocks and Palaeozoic sediments (Humboldt´s granitic rocks); Thrust Zone: Mesozoic to Cainozoic deformed sediments; Foreland basin: Cainozoic undeformed sediments (after SCHELLART 2002).

Fig.2. Axial Zone: Variscan granitoid rocks and Palaeozoic sediments (Humboldt´s granitic rocks); Thrust Zone: Mesozoic to Cainozoic deformed sediments; Foreland basin: Cainozoic undeformed sediments (after SCHELLART 2002).

The asymmetry of the Pyrenees (the estimated shortening is 70km in the south and 32km in the north), recognized already at Humboldt's times, is today explained by rotation due asymmetric mountain roots, where the Iberian plate was partially subducted under the European plate.

Bibliography:

SCHELLART, W.P. 2002: Alpine deformation at the western termination of the Axial Zone, Southern Pyrenees. In: Rosenbaum, G. and Lister, G.S.2002. Reconstruction of the evolution of the Alpine-Himalayan Orogen. Journal of the Virtual Explorer, 8, 35-55

Alexander von Humboldt

Fig.1. Geologic map and profile of the Pyrenees, after the "Berghaus-Atlas", a supplement to Humboldt's masterpiece "Kosmos" (1845-1862).

Fig.1. Geologic map and profile of the Pyrenees, after the "Berghaus-Atlas", a supplement to Humboldt's masterpiece "Kosmos" (1845-1862).

In the profile from inside to the outside of the mountains the layers are described as follows "Granitic rocks and general basement" - "transition mountains/rocks" - "secondary mountains". In the map Granite=pink, Basaltic rocks=green, Schist= grey, Clastic rocks/ Limestone= blue, Sandstone= red, Secondary Limestone= yellow, Tertiary rocks= dark-green

The German Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) studied finance and also mining engineering and became later a great self-educated explorer and naturalist. Following the tradition prevalent in Germany at the time he was educated to interpret geology with Werner's Neptunism - rocks were formed from liquids and magmatic phenomena are only of local significance.

During his travels in Europe and America he observed also active volcanoes and soon converted to Plutonism - rocks are formed from cooling lava and magmatic forces play a mayor role in shaping earth's surface.

In accordance to the theory of German geologist Leopold von Buch (1774-1835) of "volcanic bubbles" the profile shows the Pyrenees as a result of uplift by a core of magmatic rocks, bending the sedimentary layers of sandstone and limestone formations. According to this hypothesis magmatic rocks are found always as core in mountain ranges. To explain the apparent lack of Grantic rocks (coloured in pink) in the northern areas of the Pyreenes Humboldt apparently suggested selective erosion - explained by the schematic profile at the bottom of the page.

The Pyrenees are a mountain range 1500km long with an average width of 200km, the most western foothills of the Alpine-Himalayan orogenic belt. According to the modern theory of plate tectonics these mountains formed when the Iberian plate was partly subducted under the European plate, in a time period from the late Cretaceous to the Miocene (55-25 Ma).

The profile of the Pyrenees display a fan-shaped structure, with north vergent thrusts in the northern area and south vergent thrusts in the southern part.

In northwest to southeast direction the mountain range can be divided into five structural zones

- The Aquitaine foreland basin with the deformed Cretaceous sediments of the European Plate.

- The North Pyrenean thrust zone with thrust faults developed in the crystalline basement and the Mesozoic to Eocene sediments.

- The Axial zone with three mayor nappes of the crystalline basement

- The South Pyrenean thrust zone with deformed early Eocene to Miocene sediments.

- The Ebro foreland basin molassic, filled with relatively undisturbed sediments.

Fig.2. Axial Zone: Variscan granitoid rocks and Palaeozoic sediments (Humboldt´s granitic rocks); Thrust Zone: Mesozoic to Cainozoic deformed sediments; Foreland basin: Cainozoic undeformed sediments (after SCHELLART 2002).

Fig.2. Axial Zone: Variscan granitoid rocks and Palaeozoic sediments (Humboldt´s granitic rocks); Thrust Zone: Mesozoic to Cainozoic deformed sediments; Foreland basin: Cainozoic undeformed sediments (after SCHELLART 2002).

The asymmetry of the Pyrenees (the estimated shortening is 70km in the south and 32km in the north), recognized already at Humboldt's times, is today explained by rotation due asymmetric mountain roots, where the Iberian plate was partially subducted under the European plate.

Bibliography:

SCHELLART, W.P. 2002: Alpine deformation at the western termination of the Axial Zone, Southern Pyrenees. In: Rosenbaum, G. and Lister, G.S.2002. Reconstruction of the evolution of the Alpine-Himalayan Orogen. Journal of the Virtual Explorer, 8, 35-55

In Megalonyx We Trust: Jefferson's patriotic monsters

During the transition of the 18th to the 19th century earth sciences experienced a major revolution - the principles of the modern identification of rocks was introduced and sediments subdivided by the content of embedded fossils. Animals of the past apparently differed from modern ones in their abundance and in their diversity (so they could be used to subdivide the stratigraphic column) and some organisms were completely unknown to modern scholars. These observations led to a major problem: if these organisms are today unknown, are they surviving in remote regions of the globe and yet not discovered?

Classic monsters, like sea serpents along the shores of North America, the giant kraken along the shores of Africa and even sirens in the sea surrounding the United Kingdom, were spotted and depicted in books for centuries (and still today), but now naturalists responded with scepticism and reluctance to these stories - reports coming from America were soon considered as "Yankee Humbug" by European scholars.

In 1812 Georges Cuvier proclaimed that there was little hope to discover new species of large tetrapods and regarding the efforts of explorers to track down mythical animals he noted:

"…we hope that nobody thinks to search them for real, it would be like searching the animals of Daniel or the beasts of the apocalypse. Let us not even search for the mythical animals of the Persians, results of an even greater imagination."

In 1796 the third president of the United States, also president of the American Philosophical Society and naturalist Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) studied some fossil bones and a giant claw discovered during mining activities in a cave.

March 10, 1797 he presented the results to the Philosophical Society under the title "A Memoir on the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed Kind in the Western Parts of Virginia" and concluded that these remains belong to a giant felid " three times as large as the lion" which he named "Megalonyx" (great claw).

Fig.1. Engraving of the bones of the foot, toe, and claw of Megalonyx, as published in a paper by Caspar Wistar "A description of the Bones deposited by the President, in the Museum of the Society, and represented in the annexed plates." (1799). Jefferson's Megalonyx paper, which had no illustrations of the bones, was published in the same volume of American Philosophical Society Transactions.

Fig.1. Engraving of the bones of the foot, toe, and claw of Megalonyx, as published in a paper by Caspar Wistar "A description of the Bones deposited by the President, in the Museum of the Society, and represented in the annexed plates." (1799). Jefferson's Megalonyx paper, which had no illustrations of the bones, was published in the same volume of American Philosophical Society Transactions.

Jefferson, in accordance to the naturalistic knowledge of the time, believed that in nature no species could became extinct, so he continued in his report:

"In the present interior of our continent there is surely space and range enough for elephants and lions, if in that climate they could subsist; and for the mammoth and megalonyxes who may subsist there. Our entire ignorance of the immense country to the West and North-West, and of its contents, does not authorise us so say what is does not contain."

Jefferson based this conclusion in part on anecdotes of woodsmen being terrorized by a large cat-like animal in the wilderness and the presumed representations of lions in Indian rock paintings (possibly the American lion Panthera atrox ?).

However the most important argument for Jefferson was a theological one: if a species can become extinct in a perfect divine creation such a creation can't possibly be so perfect all along, the continuous loss of species would inevitable lead to the end of this imperfect creation.

"The movements of nature are in a never ending circle. The animal species which has once been put into a train of motion, is still probably moving in that train. For if one link in nature's chain might be lost, another and another might be lost, till this whole system of things should be evanish by piece-meal; a conclusion not warranted by the local disappearance of one or two species of animals, and opposed by the thousands and thousands of instances of the renovating power constantly exercised by nature for the reproduction of all her subjects, animal, vegetable, and mineral."

Fig.2. Sketch of the so called "Madrid skeleton" sent to Jefferson by tradesman William Carmichael in 1789. A large skeleton was found near Buenos Aires, in his letter Carmichael notes "I also inclose…a discription of the Skeleton of an Animal discovered lately in Spanish America. I supposed these to be objects of Curiosity to you,…" Jefferson recognized that the bones and claw he had attributed to his large cat Megalonyx were comparable to these of this animal, described in 1796 by Cuvier as Megatherium.

Fig.2. Sketch of the so called "Madrid skeleton" sent to Jefferson by tradesman William Carmichael in 1789. A large skeleton was found near Buenos Aires, in his letter Carmichael notes "I also inclose…a discription of the Skeleton of an Animal discovered lately in Spanish America. I supposed these to be objects of Curiosity to you,…" Jefferson recognized that the bones and claw he had attributed to his large cat Megalonyx were comparable to these of this animal, described in 1796 by Cuvier as Megatherium.

Jefferson also collected all sorts of information about large mammals and bones to support his view of the new continent as populated with fascinating animals as the old continent and rest of the world.

Jefferson also had some political motives to support the existence of large and ferocious animals in the U.S.

In his works the eminent France naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788) proposed a theory to explain the worldwide distribution of animal species: from environmental optimal centres species would spread all over the globe, however degenerating in areas with less favourable climate or environment - and according to Buffon the fauna of America was an perfect example of such a degenerated European and African fauna.

This worldview not only offended Jefferson's personal feelings, but also seriously damaged the reputation of the young United States of America. The U.S. needed the political and financial support of France during the Revolutionary Wars (1775-1783), Buffon was however popularizing the perception that "America is an excessively cold and humid continent where big animals cannot survive, domestic animals become scrawny, and men become stupid and lose their sexual vigor" (ROWLAND 2009)

In spring 1785 Jefferson published anonymous his "Notes on the State of Virginia", where he discussed naturalistic and also political facts of this state. In various lists he compared the mammals of the new continent to the mammals of the old continent, concluding that the body mass and diversity of American animals was far superior then envisaged by Buffon. He also reaffirmed his view on the impossibility of extinction:

"The bones of the Mammoth which have been found in America, are as large as those found in the old world. It may be asked, why I insert the Mammoth, as if it still existed? I ask in return, why I should omit it, as if it did not exist?

Such is the economy of nature, that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; of her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken. To add to this, the traditionary testimony of the Indians, that this animal still exists in the northern and western parts of America, would be adding the light of a taper to that of the meridian sun. Those parts still remain in their aboriginal state, unexplored and undisturbed by us, or by others for us. He may as well exist there now, as he did formerly where we find his bones."

In 1803 Jefferson organized the famous Lewis and Clark expedition; apart political important tasks, like the geographical exploration of Louisiana and the search for a navigable passage to the Pacific, this expedition should also dig for fossils and search for the supposed unknown large tetrapods of North America.

Jefferson in his lifetime never really embraced the theory of extinction, probably as a results of personal religious beliefs and political agenda - only in the mid 19th century extinction will become a scientific fact.

Bibliography:

ROWLAND, S.M. (2009): Thomas Jefferson, extinction, and the evolving view of Earth history in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In ROSENBERG, G.D., ed., The Revolution in Geology from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment: Geological Society of America Memoir 203: 225-246

Online Resources:

MURPHY, D.C. (): Fossils and Extinction. The Academy of Natural Sciences. (Accessed 15.08.2011)

MURPHY, D.C. (): Discovering The Great Claw: Part 1 - The Giant Cat. The Academy of Natural Sciences. (Accessed 15.08.2011)

Classic monsters, like sea serpents along the shores of North America, the giant kraken along the shores of Africa and even sirens in the sea surrounding the United Kingdom, were spotted and depicted in books for centuries (and still today), but now naturalists responded with scepticism and reluctance to these stories - reports coming from America were soon considered as "Yankee Humbug" by European scholars.

In 1812 Georges Cuvier proclaimed that there was little hope to discover new species of large tetrapods and regarding the efforts of explorers to track down mythical animals he noted:

"…we hope that nobody thinks to search them for real, it would be like searching the animals of Daniel or the beasts of the apocalypse. Let us not even search for the mythical animals of the Persians, results of an even greater imagination."

In 1796 the third president of the United States, also president of the American Philosophical Society and naturalist Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) studied some fossil bones and a giant claw discovered during mining activities in a cave.

March 10, 1797 he presented the results to the Philosophical Society under the title "A Memoir on the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed Kind in the Western Parts of Virginia" and concluded that these remains belong to a giant felid " three times as large as the lion" which he named "Megalonyx" (great claw).

Fig.1. Engraving of the bones of the foot, toe, and claw of Megalonyx, as published in a paper by Caspar Wistar "A description of the Bones deposited by the President, in the Museum of the Society, and represented in the annexed plates." (1799). Jefferson's Megalonyx paper, which had no illustrations of the bones, was published in the same volume of American Philosophical Society Transactions.

Fig.1. Engraving of the bones of the foot, toe, and claw of Megalonyx, as published in a paper by Caspar Wistar "A description of the Bones deposited by the President, in the Museum of the Society, and represented in the annexed plates." (1799). Jefferson's Megalonyx paper, which had no illustrations of the bones, was published in the same volume of American Philosophical Society Transactions.

Jefferson, in accordance to the naturalistic knowledge of the time, believed that in nature no species could became extinct, so he continued in his report:

"In the present interior of our continent there is surely space and range enough for elephants and lions, if in that climate they could subsist; and for the mammoth and megalonyxes who may subsist there. Our entire ignorance of the immense country to the West and North-West, and of its contents, does not authorise us so say what is does not contain."

Jefferson based this conclusion in part on anecdotes of woodsmen being terrorized by a large cat-like animal in the wilderness and the presumed representations of lions in Indian rock paintings (possibly the American lion Panthera atrox ?).

However the most important argument for Jefferson was a theological one: if a species can become extinct in a perfect divine creation such a creation can't possibly be so perfect all along, the continuous loss of species would inevitable lead to the end of this imperfect creation.

"The movements of nature are in a never ending circle. The animal species which has once been put into a train of motion, is still probably moving in that train. For if one link in nature's chain might be lost, another and another might be lost, till this whole system of things should be evanish by piece-meal; a conclusion not warranted by the local disappearance of one or two species of animals, and opposed by the thousands and thousands of instances of the renovating power constantly exercised by nature for the reproduction of all her subjects, animal, vegetable, and mineral."

Fig.2. Sketch of the so called "Madrid skeleton" sent to Jefferson by tradesman William Carmichael in 1789. A large skeleton was found near Buenos Aires, in his letter Carmichael notes "I also inclose…a discription of the Skeleton of an Animal discovered lately in Spanish America. I supposed these to be objects of Curiosity to you,…" Jefferson recognized that the bones and claw he had attributed to his large cat Megalonyx were comparable to these of this animal, described in 1796 by Cuvier as Megatherium.

Fig.2. Sketch of the so called "Madrid skeleton" sent to Jefferson by tradesman William Carmichael in 1789. A large skeleton was found near Buenos Aires, in his letter Carmichael notes "I also inclose…a discription of the Skeleton of an Animal discovered lately in Spanish America. I supposed these to be objects of Curiosity to you,…" Jefferson recognized that the bones and claw he had attributed to his large cat Megalonyx were comparable to these of this animal, described in 1796 by Cuvier as Megatherium.

Jefferson also collected all sorts of information about large mammals and bones to support his view of the new continent as populated with fascinating animals as the old continent and rest of the world.

Jefferson also had some political motives to support the existence of large and ferocious animals in the U.S.

In his works the eminent France naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788) proposed a theory to explain the worldwide distribution of animal species: from environmental optimal centres species would spread all over the globe, however degenerating in areas with less favourable climate or environment - and according to Buffon the fauna of America was an perfect example of such a degenerated European and African fauna.

This worldview not only offended Jefferson's personal feelings, but also seriously damaged the reputation of the young United States of America. The U.S. needed the political and financial support of France during the Revolutionary Wars (1775-1783), Buffon was however popularizing the perception that "America is an excessively cold and humid continent where big animals cannot survive, domestic animals become scrawny, and men become stupid and lose their sexual vigor" (ROWLAND 2009)

In spring 1785 Jefferson published anonymous his "Notes on the State of Virginia", where he discussed naturalistic and also political facts of this state. In various lists he compared the mammals of the new continent to the mammals of the old continent, concluding that the body mass and diversity of American animals was far superior then envisaged by Buffon. He also reaffirmed his view on the impossibility of extinction:

"The bones of the Mammoth which have been found in America, are as large as those found in the old world. It may be asked, why I insert the Mammoth, as if it still existed? I ask in return, why I should omit it, as if it did not exist?

Such is the economy of nature, that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; of her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken. To add to this, the traditionary testimony of the Indians, that this animal still exists in the northern and western parts of America, would be adding the light of a taper to that of the meridian sun. Those parts still remain in their aboriginal state, unexplored and undisturbed by us, or by others for us. He may as well exist there now, as he did formerly where we find his bones."

In 1803 Jefferson organized the famous Lewis and Clark expedition; apart political important tasks, like the geographical exploration of Louisiana and the search for a navigable passage to the Pacific, this expedition should also dig for fossils and search for the supposed unknown large tetrapods of North America.

Jefferson in his lifetime never really embraced the theory of extinction, probably as a results of personal religious beliefs and political agenda - only in the mid 19th century extinction will become a scientific fact.

Bibliography:

ROWLAND, S.M. (2009): Thomas Jefferson, extinction, and the evolving view of Earth history in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In ROSENBERG, G.D., ed., The Revolution in Geology from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment: Geological Society of America Memoir 203: 225-246

Online Resources:

MURPHY, D.C. (): Fossils and Extinction. The Academy of Natural Sciences. (Accessed 15.08.2011)

MURPHY, D.C. (): Discovering The Great Claw: Part 1 - The Giant Cat. The Academy of Natural Sciences. (Accessed 15.08.2011)

Onkalo

Onkalo - the cave - is the name given to a subterranean facility being built deep inside massive gneiss lens surrounded by schist in southern Finland. Once finished in 2020 it will act as permanent repository for highly radioactive nuclear waste.

When its capacity is exhausted - in estimated 100 years - it must be sealed off for at least the next 100.000 years…Into Eternity is a documentary film realized in 2009 that explores the gloomy threat of a place that can never be forgotten and at the same time should ever be feared by future generations….

Channeled Scabland and the Spokane Flood

The landscape of eastern Washington shows some unique landforms that already in the early 20th century fascinated geologists:

"No one with an eye for land forms can cross eastern Washington in daylight without encountering and being impressed by the "scabland." Like great scars marring the otherwise fair face to the plateau are these elongated tracts of bare, black rock carved into mazes of buttes and canyons. Everybody on the plateau knows scabland…[]…The popular name is a metaphor. The scablands are wounds only partially healed - great wounds in the epidermis of soil with which Nature protects the underlying rock…[]…The region is unique: let the observer take wings of the morning to the uttermost parts of the earth: he will nowhere find its likeness."

J Harlen Bretz 1928

American geologist J Harlen Bretz (1882-1981) proposed in 1919, in winter of 1922 and in various papers (here and here and here) in 1923 to 1925 a controversial hypothesis to explain the landscape - a flood episode of very great extant and amount:

"The volume of the invading waters much exceeds the capacity of the existing streamways. The valleys entered become river channels, they brim over into neighboring ones, and minor divides within the system are crossed in hundreds of places.

The topographic features produced during this episode are wholly river-bottom modifications of the invaded and overswept drainage network of hills and valleys. Hundreds of cataract ledges, of basins and canyons eroded into bed rock, of isolated buttes of the bed rock, of gravel bars piled high above the valley floors, and of island hills of the weaker overlying formations are left at the cessation of this episode…[]…Everywhere the record is of extraordinary vigorous sub-fluvial action. The physiographic expression of the region is without parallel; it is unique, this channelled scabland of the Columbia Plateau."

J Harlen Bretz 1928

The fluvial or glacial origin of the scablands was already clear from the observed features - deep incised gorges, steep cliffs or former waterfalls and cataracts, hanging valleys, eroded bedrock and widespread erratic boulders.

In 1838 Reverend Samuel Parker explained the scablands as the former river valleys of the Columbia River and in 1882 during a topographic survey Lieutenant T.W. Symons proposed that the river changed direction by a former ice-shield blocking its path. In alternative Thomas Condon in 1902 imagined a flood coming from the sea with the erratic boulders transported by drift ice.

Fig.1. Bristow, H.G. (1872) "The world before the deluge by Louis Figuier", showing the transport of boulders enclosed in drift ice.

Fig.1. Bristow, H.G. (1872) "The world before the deluge by Louis Figuier", showing the transport of boulders enclosed in drift ice.

Bretz in 1919 proposed a freshwater flood coming from the interior of the North American continent and following in part the path of the late Pleistocene Columbia River. However he couldn't explain the origin of the water - there were two possibilities, a rapid warming of the climate causing the melting of the Laurentian ice shield or a "jokulloup" caused by volcanic eruptions under the ice.

Fig.2. Hypothesized submergence map of the lower Columbia River system, after BRETZ 1919.

Fig.2. Hypothesized submergence map of the lower Columbia River system, after BRETZ 1919.

The proposed hypothesis arouse so much interest that on 12, January 1927 a meeting of the Geological Society of Washington with the title "Channeled Scabland and the Spokane Flood" was organized.

The main criticism in the following discussion concentrated on the problem of the estimated huge amount of water required (not explainable by the proposed mechanisms) and the short interval involved in the formation of the scablands (the various mapped spillways could have formed at various moments).

Research done and published some years previously by geologist Joseph T. Pardee (1871-1960) helped to solve this mystery. Pardee had mapped the outlines of a gigantic ice-dammed lake, comprising an area extending from today's north-western Washington to Idaho and Montana, which he named Lake Missoula (in fact there were various lakes dammed up by various ice lobes and named today Lake Missoula and Columbia/Spokane).

In 1933 the International Geological Congress field trip led to the Channeled Scablands, dividing the community in supporters and opponents of the flood-hypothesis.

In 1940 the American Association for the Advancement of Science met in Seattle, in the session "Quaternary Geology of the Pacific Northwest" most contributions were against the flood, but again Pardee proposed an interesting paper entitled "Ripple marks (?) in glacial Lake Missoula", where he described extraordinary large gravel ripples (15m high and with a wavelength of 150m) found in a basin of Montana. These ripple marks were a strong evidence supporting a catastrophic flood draining Lake Missoula, providing the necessary great amounts of water to explain the erosion of the scablands.

In the following decades Bretz continued to collect geologic information about the extant of the Spokane flood and finally in the decade of 1960 to 1970 the flood hypothesis convinced definitively the geologic community.

Bibliography:

BAKER, V.R. (2008): The Spokane Flood debates: historical background and philosophical perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications Vol. 301: 33-50

BAKER, V.R. (2009): The Channeled Scabland: A Retrospective. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. Vol.37(6): 1-19

BRETZ, J. H. (1928): Channeled Scabland of eastern Washington. Geographical Review, 18: 446–477

"No one with an eye for land forms can cross eastern Washington in daylight without encountering and being impressed by the "scabland." Like great scars marring the otherwise fair face to the plateau are these elongated tracts of bare, black rock carved into mazes of buttes and canyons. Everybody on the plateau knows scabland…[]…The popular name is a metaphor. The scablands are wounds only partially healed - great wounds in the epidermis of soil with which Nature protects the underlying rock…[]…The region is unique: let the observer take wings of the morning to the uttermost parts of the earth: he will nowhere find its likeness."

J Harlen Bretz 1928

American geologist J Harlen Bretz (1882-1981) proposed in 1919, in winter of 1922 and in various papers (here and here and here) in 1923 to 1925 a controversial hypothesis to explain the landscape - a flood episode of very great extant and amount:

"The volume of the invading waters much exceeds the capacity of the existing streamways. The valleys entered become river channels, they brim over into neighboring ones, and minor divides within the system are crossed in hundreds of places.

The topographic features produced during this episode are wholly river-bottom modifications of the invaded and overswept drainage network of hills and valleys. Hundreds of cataract ledges, of basins and canyons eroded into bed rock, of isolated buttes of the bed rock, of gravel bars piled high above the valley floors, and of island hills of the weaker overlying formations are left at the cessation of this episode…[]…Everywhere the record is of extraordinary vigorous sub-fluvial action. The physiographic expression of the region is without parallel; it is unique, this channelled scabland of the Columbia Plateau."

J Harlen Bretz 1928

The fluvial or glacial origin of the scablands was already clear from the observed features - deep incised gorges, steep cliffs or former waterfalls and cataracts, hanging valleys, eroded bedrock and widespread erratic boulders.

In 1838 Reverend Samuel Parker explained the scablands as the former river valleys of the Columbia River and in 1882 during a topographic survey Lieutenant T.W. Symons proposed that the river changed direction by a former ice-shield blocking its path. In alternative Thomas Condon in 1902 imagined a flood coming from the sea with the erratic boulders transported by drift ice.

Fig.1. Bristow, H.G. (1872) "The world before the deluge by Louis Figuier", showing the transport of boulders enclosed in drift ice.

Fig.1. Bristow, H.G. (1872) "The world before the deluge by Louis Figuier", showing the transport of boulders enclosed in drift ice.Bretz in 1919 proposed a freshwater flood coming from the interior of the North American continent and following in part the path of the late Pleistocene Columbia River. However he couldn't explain the origin of the water - there were two possibilities, a rapid warming of the climate causing the melting of the Laurentian ice shield or a "jokulloup" caused by volcanic eruptions under the ice.

Fig.2. Hypothesized submergence map of the lower Columbia River system, after BRETZ 1919.

Fig.2. Hypothesized submergence map of the lower Columbia River system, after BRETZ 1919.The proposed hypothesis arouse so much interest that on 12, January 1927 a meeting of the Geological Society of Washington with the title "Channeled Scabland and the Spokane Flood" was organized.

The main criticism in the following discussion concentrated on the problem of the estimated huge amount of water required (not explainable by the proposed mechanisms) and the short interval involved in the formation of the scablands (the various mapped spillways could have formed at various moments).

Research done and published some years previously by geologist Joseph T. Pardee (1871-1960) helped to solve this mystery. Pardee had mapped the outlines of a gigantic ice-dammed lake, comprising an area extending from today's north-western Washington to Idaho and Montana, which he named Lake Missoula (in fact there were various lakes dammed up by various ice lobes and named today Lake Missoula and Columbia/Spokane).

In 1933 the International Geological Congress field trip led to the Channeled Scablands, dividing the community in supporters and opponents of the flood-hypothesis.

In 1940 the American Association for the Advancement of Science met in Seattle, in the session "Quaternary Geology of the Pacific Northwest" most contributions were against the flood, but again Pardee proposed an interesting paper entitled "Ripple marks (?) in glacial Lake Missoula", where he described extraordinary large gravel ripples (15m high and with a wavelength of 150m) found in a basin of Montana. These ripple marks were a strong evidence supporting a catastrophic flood draining Lake Missoula, providing the necessary great amounts of water to explain the erosion of the scablands.

In the following decades Bretz continued to collect geologic information about the extant of the Spokane flood and finally in the decade of 1960 to 1970 the flood hypothesis convinced definitively the geologic community.

Bibliography:

BAKER, V.R. (2008): The Spokane Flood debates: historical background and philosophical perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications Vol. 301: 33-50

BAKER, V.R. (2009): The Channeled Scabland: A Retrospective. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. Vol.37(6): 1-19

BRETZ, J. H. (1928): Channeled Scabland of eastern Washington. Geographical Review, 18: 446–477

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)